|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

The vast majority of the primary sources that bear witness to medieval English towns and the lives of the men and women who resided in them each focus on some particular aspect or event. General descriptions of any individual towns are rare, as are surveys or reviews of English towns generally. We do possess a few examples of these, however, and three are given here. Two happen to be roughly contemporary with each other, from the period when we are just beginning to see boroughs emerging as distinctive entities in the social and economic fabric. Furthermore, they present contrasting viewpoints on urban society: one pro, one con. The third comes at the close of the Middle Ages.

|

An imaginary town, in idyllic rural setting, with typical features: riverside location; enclosing wall with gates controlling the main entrances/exits; high street, connecting to a bridge across the river; parish church; the square on the left side may even represent a marketplace. From the Book of Hours of Henry Beauchamp, Duke of Warwick (before 1446). |

For the earlier pair we have two monks to thank – not surprisingly, given the limitations of literacy in that period. They are unlikely to have ever had contact with one another, but each gives us a lively and entertaining perspective on English towns of the late twelfth century. The third description comes from an outsider, probably a member of a diplomatic embassy sent by Venice to London.

The lesser-known of the monks, both today and in the Middle Ages, is Richard de Devizes, a monk of St. Swithun's, the priory of Winchester's cathedral. He was presumably born at the place from which derives his surname, a small town in Wiltshire some 35 miles northwest of Winchester and, again presumably as a monk at Winchester throughout his adult life, may well not ever have travelled beyond that part of the country. Nonetheless, Winchester was an important city at that time and attracted visitors from all parts, and Richard doubtless heard news, rumours and opinions about various English towns – many of his criticisms have the tone of put-downs of the type communicated in casual conversation. Richard's brief critique of English towns is outside of the mainstream of the theme of his chronicle, and it reflects both a measure of scorn for urban society that would have been echoed by many monks (except perhaps for those of more worldly tastes) and yet an affection for his own adopted home-town.

The better-known writer is William FitzStephen, who prefaced his biography of Thomas Becket with a depiction of London during the reign of Henry II. FitzStephen, according to his own claim, served Becket both in the latter's role of chancellor, by preparing legal documents and assisting in the hearing of petitions, and in his role of archbishop, as a chaplain. He likewise claimed to be one of the three clerics who did not desert Becket during his assassination (1170). Despite or perhaps because of this, he seems to have won the favour of Henry II (whom he avoided blaming in his account of the murder), if he is the same William FitzStephen who in 1171 was appointed sheriff of Gloucestershire and later (from 1176) served as an itinerant royal justice; of that identification we cannot be certain. The biography was written at some point in the ten or twelve years following Becket's death.

The reason for a description of London preceding the biography of Becket was, ostensibly, that Becket was – like FitzStephen himself – a Londoner, being the son of Gilbert Becket, a Rouen merchant who settled in London and became an important enough citizen to serve as a sheriff of the city. Yet it is less Becket's association with the city and more FitzStephen's own that comes through in the description, which could easily stand by itself – and so, stripped of the biography, it does in some surviving versions, including one incorporated into London's Liber Custumarum. He provides us with a look at London through rose-tinted glasses, for his remembrances of the city are largely those of exuberant youth, full of wonder at metropolitan life, and eager to enjoy its pleasures. Although he does talk in general terms about aspects of the city, he also focuses on particular places, particular events – doubtless calling up the features that most embedded themselves in his memory.

It is easy to be tempted today, given the relative ease and luxuries of twenty-first century living and working conditions, to view life in medieval towns as dirty, harsh, unpleasant, and short. We must remember that this is only a perspective, albeit one not without some merit. It has an advocate in Richard de Devizes, if in tongue-in-cheek fashion; his harshest words are for London, not only because as England's sole cosmopolitan city it was the biggest den of iniquity, but also because its efforts to create a revolutionary commune in 1191 had filled him with a disgust founded on fear. FitzStephen's perspective is quite different, if naive where Devizes' is cynical; his fondness for London and his high regard for its amenities and its joie de vivre are clear enough. He has little bad to say of London, other than references to its drunks and its vulnerability to fire. His account is a rhapsodic expression of that civic pride which historians must otherwise deduce from more formal or more impersonal echoes.

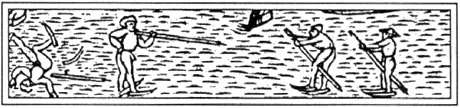

Yet for all this, and despite some minor flights of rhetoric in which the author tries to display his knowledge of classical authors (a trait common to writers of that time, although the knowledge was often acquired indirectly), FitzStephen's description is credible, as indeed Devizes' chronicle is believed to be, once the satirical elements are taken into account. FitzStephen has not exaggerated for the sake of hyperbole, only for literary effect or on the basis of second-hand information which he accepts unquestioningly. Much of what he speaks about is corroborated from other evidence; the ice jousting, for example, is depicted in a medieval illustration. We can well imagine that he was an eye-witness to most of what he portrays, as well as a participant in the schoolboy debating contests he recounts with some enthusiasm. The description ranges from the macrocosm of the quality of the citizens to the microcosm of the cookshop on the quayside and the Smithfield horse-races, which surely reflect fond memories of the author himself. The popularity of fast-food and racetracks is no modern phenomenon.

This late 15th century woodcut shows skaters

engaged

in the kinds of activities

described by FitzStephen.

There is a good deal we can recognize in FitzStephen's characterization of twelfth-century London society that rings true for city life in the twentieth century, while Devizes' account similarly reflects many of today's prejudices towards the urban setting. Plus ça change...

|

|

main menu |

|

|

||

|

Encyclopedia | Library | Reference | Teaching | General | Links | Search | About ORB | HOME The contents of ORB are copyright © 2003 Kathryn M. Talarico except as otherwise indicated herein. |