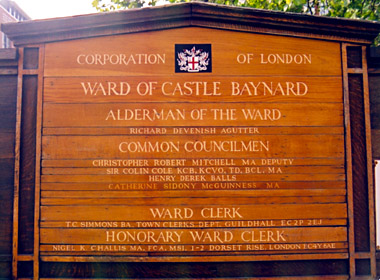

Noticeboard identifying the incumbents of a ward

photo © S. Alsford

For most of the late medieval period the ward was the constituency in London. Only a few other English towns were populous enough to warrant a division of the electorate on that kind of basis, and they did not use the system to the same extent as in London. There the ward had long been a unit for defence, police and judicial administration, and other administrative concerns (e.g. sanitation).

The wardmoot was where London citizens met to choose their aldermen and their Common Councillors. Ward meetings, as administrative institutions, were supposed to be attended by all lay male adult residents. Whether electoral meetings were attended by such a large group, we do not know, and the holding of some elections of aldermen in the Guildhall is suggestive of less than full participation.

In fact, other than in periods of political radicalism, the aldermen tended to hold office for life, or until they chose to step down, or (less commonly) disgraced themselves in the eyes of their peers. This apparently unwritten custom, not unchallenged, was overthrown in favour of annual election by the political fervour harnessed by John Northampton in the 1370s and '80s. But this reform met with its own reversal when conservative forces regained control. Annual election was allowed to go by the boards and in 1394 was formally abolished by Parliament. In 1397 popular influence over the selection of aldermen was further diminished by an ordinance allowing the electorate only to nominate two candidates, with the mayor and aldermen making the final choice; the number was subsequently altered to four.

So the opportunity of the electorate came infrequently, as regards the selection of London aldermen. And when it did come, the electors almost invariably chose to shoulder the burden on a member of the "ruling class", if we may use such a term to describe the wealthier members of the community, whose interests and outlook were more closely aligned with each other than with lesser residents who earned a more meagre living by the skill or labour of their hands. Probably in no town was collective decision-making by the community (or, rather, those adult male members of the community qualified, usually by having become freemen, to participate in political assemblies) more than a principle; practical government, by its nature, tends to devolve to much smaller groups.

London's Common Council emerged out of ad hoc committees of citizens brought together to address specific problems and assemblies for more general business at which representatives were summoned from the wards, as far back as the late thirteenth century. Early in the next century – again a period of the conflict of different political perspectives – the principles were declared that each alderman was answerable to the constituency of his ward, and that mayor and aldermen collectively were answerable to the citizenry as a whole; from which stemmed an ordinance requiring unanimous consent of an assembly to the common seal being appended to any document of importance. The constitution of this assembly was left to experiment; it may be that the councillors were freely elected by ward residents, or possibly the alderman of each ward had some influence over the selection.

Short-lived attempts to have Common Councillors selected by the craft gilds rather than the wards did serve to introduce men lower down the social scale into city government. But by the close of the fourteenth century, election had been returned to the wards. The number of councillors per ward was made proportional to the size of the ward.

This situation has remained the same over the last half-millennium, until very recently,* with councillors elected by freemen (a status now open to women) in ward meetings, and aldermen serving for "life" (retirement at age 70). The aldermen, who still wear fur-trimmed scarlet gowns on ceremonial occasions, continue to have important jurisdiction in their wards; but as a body, are less important today than they were in the Middle Ages. The Court of Common Council, which includes the aldermen, is the principal decision-making body. Similarly, the mayor is still elected, as he was by the close of the Middle Ages, by a select number of citizens specially summoned: the Common Councillors and representatives of the livery companies; and still they nominate two candidates, from whom the aldermen choose the new mayor. The essential shape of London's government, as well as that of its bureaucracy, was thus established by the end of the medieval period.

We could say the same for many other English towns, notwithstanding reforms of the Victorian era. A form of limited representative government was settled on – London's full council sometimes exceeding two hundred participants, while those of other towns where multi-tiered councils were established often exceeded sixty. This constitutional solution offered the hope of stability, as opposed to the risks of turbulence and demagoguery of a more populist kind of democracy. By broadening the base of participation in government somewhat, the ruling class appears to have won the support of most of the leading members of the crafts, thus depriving the disempowered lesser townsmen of the leadership that they would have needed to alter the situation.

At the same time, urban politics was less dominated than it had been in thirteenth and fourteenth centuries by a small number of powerful local families, furnishing leaders across several generations. Due in part to restrictions on re-election or consecutive terms, but also to social and economic changes, executive office was spread among a larger number of the ruling class.

* Reforms given royal assent in November 2002 allow city businesses to have the vote (a situation reminiscent of the medieval political involvement of craft gilds), while the aldermen's posts are now to be subject to elections every few years. Boundaries of the 25 wards are being reviewed.